The Other Boleyn Girl (2008 film)

The Other Boleyn Girl (2008 film)

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

| The Other Boleyn Girl | |

|---|---|

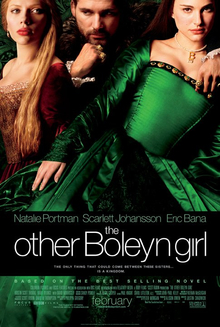

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Justin Chadwick |

| Produced by | Alison Owen |

| Screenplay by | Peter Morgan |

| Based on | The Other Boleyn Girl by Philippa Gregory |

| Starring | Natalie Portman Scarlett Johansson Eric Bana Jim Sturgess Kristin Scott Thomas Mark Rylance David Morrissey Benedict Cumberbatch Eddie Redmayne |

| Music by | Paul Cantelon |

| Cinematography | Kieran McGugan |

| Edited by | Paul Knight Carol Littleton |

Production company | BBC Films Relativity Media |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures (United States) Focus Features (international) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 115 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $35 million |

| Box office | $77.7 million |

The Other Boleyn Girl is a 2008 historical romantic drama film directed by Justin Chadwick. The screenplay by Peter Morgan was adapted from Philippa Gregory’s 2001 novel of the same name. It is a fictionalized account of the lives of 16th-century aristocrats Mary Boleyn, one-time mistress of King Henry VIII, and her sister, Anne, who became the monarch's ill-fated second wife, though much history is distorted.

Production studio BBC Films also owns the rights to adapt the sequel novel, The Boleyn Inheritance, which tells the story of Anne of Cleves, Catherine Howard and Jane Parker.[1]

Contents

1 Plot

2 Cast

3 Locations

4 Historical accuracy

5 Release

5.1 Theatrical

5.2 Home media

6 Critical reception

7 See also

8 References

9 External links

Plot[edit]

King Henry VIII's marriage to Catherine of Aragon is troubled as she has not produced a living male heir to the throne, having only one surviving child, Mary. Mary Boleyn marries William Carey. After the festivities, Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk and his brother-in-law Thomas Boleyn plan to install Boleyn's eldest daughter, Anne Boleyn, as the king's mistress, with the hope that Anne will bear him a son and that she'll be able to improve her family's wealth and status. Anne's mother, Lady Elizabeth Boleyn, is disgusted by the plot, but Anne eventually agrees as a way to please her father and uncle.

While visiting the Boleyn estate, Henry is injured in a hunting accident that was indirectly caused by Anne. Urged by her scheming uncle, Mary nurses Henry. Henry becomes smitten with Mary and invites her to court, to which Mary and her husband reluctantly agree, aware that the king has invited her because he desires her. Mary and Anne become ladies-in-waiting to Queen Catherine and Henry sends William Carey abroad on an assignment. Separated from her husband, Mary begins an affair with the king and finds herself falling in love with him. Anne secretly marries the nobleman Henry Percy, although he is already betrothed to Lady Mary Talbot. Anne confides in her brother, George Boleyn, about the marriage. Overjoyed, George proceeds to tell Mary. Fearing Anne will ruin the Boleyn family by marrying such a prominent earl without the king's consent, Mary alerts her father and uncle. They confront Anne, forcibly annul the marriage, and exile her to France.

Mary eventually becomes pregnant with Henry's child. Her family receives new grants and estates, their debts are paid, and Henry arranges George's marriage to Jane Parker. When Mary nearly suffers a miscarriage, she is confined to bed until her child is born. Norfolk recalls Anne to England and is tasked to keep Henry's attention from wandering to another rival while Mary is confined. Believing that Mary had her exiled to increase her own status, Anne gets back at her by successfully winning Henry over. When Mary gives birth to a son, Henry Carey, Thomas and Norfolk are overjoyed, but the celebration is short lived as Anne tells Henry that the baby is born a bastard and that, for her to accept his advances, he must stop talking to Mary. This infuriates Norfolk, as the king refuses to acknowledge the child as his heir. Henry then has Mary sent to the countryside at Anne's request. Shortly after, Mary is widowed.

Anne encourages Henry to break from the Catholic Church when the Pope refuses to annul his marriage to Queen Catherine. Henry succumbs to Anne's demands, declares himself Supreme Head of the Church of England, and gets Cardinal Thomas Wolsey to annul the marriage. Having fulfilled Anne's requests, Henry comes to Anne's room but she refuses to have sex with him until they are married. In a fit of rage, he rapes her. A pregnant Anne marries Henry to please her family and becomes Queen of England. As a wife, Henry slowly starts despising her, and, as a queen, she is hated by the public, being deemed a witch. Despite the birth of a healthy daughter, Elizabeth, Henry blames Anne for not producing a son and begins courting Jane Seymour in secret.

After Anne suffers the miscarriage of a son, she begs George to have sex with her to replace the child she lost, for fear of being passed over by Henry and burned as a witch. George at first reluctantly agrees, realizing that it is Anne's only hope, but they do not go through with it. However, George's neglected wife Jane, under orders from Norfolk to spy on Anne, witnesses enough of their encounter to become suspicious. She reports what she has seen, and both Anne and George are arrested. The two are found guilty and sentenced to death for treason, adultery, and incest. Distraught by the news of the execution of George, his mother disowns her husband and brother, vowing never to forgive them for what their greed has done to her children.

After Mary learns that she was late for George's execution, she returns to court to plead for Anne's life. Believing that Henry will spare her sister, she leaves to see Anne right before the scheduled execution. Anne asks Mary to take care of her daughter Elizabeth if anything should happen to her. Mary watches from the crowd as Anne makes her final speech, waiting for the execution to be cancelled as Henry promised. A letter from Henry is given to Mary, warning her not to come to his court any more, and implicitly revealing his decision to execute Anne after all. Ten days after Anne's execution, Henry and Jane Seymour are married. Norfolk is imprisoned and the next three generations of his family are executed for treason in their turn. Mary marries William Stafford and they have two children, Anne and Edward. Mary takes an active role in raising Anne's daughter Elizabeth, who grows up to become the future Queen of England, and reigns for 44 years.

Cast[edit]

Natalie Portman as Anne Boleyn. Portman was attracted to the role because it was a character that she "hadn’t played before", and describes Anne as "strong, yet she can be vulnerable and she's ambitious and calculating and will step on people but also feels remorse for it". One month before filming began, Portman started taking daily classes to master the English accent under dialect coach Jill McCulloch, who also stayed on set throughout the filming.[2] This was her second film to use her English accent after V for Vendetta.

Scarlett Johansson as Mary Boleyn. Johansson expressed concern over the film being "such a melodramatic tale". In response to critics being sceptical about the film featuring American actresses as major British characters, Johansson said, "The three foreign actors will be using English accents. I'll take away the eyebrows and the make-up and you won't notice I'm American".[3]

Eric Bana as Henry VIII of England. Bana commented that he was surprised upon being offered the role, and describes the character of Henry as "a man who was somewhat juvenile and driven by passion and greed", and that he interpreted the character as "this man who was involved in an incredibly intricate, complicated situation, largely through his own doing".[4] In preparation for the role, Bana relied mostly on the script to come up with his own version of the character, and he "deliberately stayed away" from other portrayals of Henry in films because he found it "too confusing and restricting".[5]

Jim Sturgess as George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford. Though the three siblings are all very tight-knit, George and Anne are closest. George supports and loves Anne for her rebellious and unconventional attitude. He is forced to marry Jane Parker. George is often viewed as the most vulnerable and probably the kindest of the siblings.

Kristin Scott Thomas as Elizabeth Boleyn, Countess of Wiltshire and Ormond

Mark Rylance as Thomas Boleyn, Earl of Wiltshire and Ormond

David Morrissey as Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk

Benedict Cumberbatch as William Carey

Oliver Coleman as Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland

Ana Torrent as Catherine of Aragon

Eddie Redmayne as William Stafford

Juno Temple as Jane Parker

- Iain Mitchell as Thomas Cromwell

Andrew Garfield as Francis Weston

- Corinne Galloway as Jane Seymour

- Constance Stride as young Mary Tudor

Maisie Smith as young Elizabeth Tudor

Alfie Allen as the King's Messenger

Locations[edit]

Much of the filming took place in Kent, England, though Hever Castle was not used, despite being the original household of Thomas Boleyn and family from 1505–1539. The Baron's Hall at Penshurst Place featured, as did Dover Castle, which stood in for the Tower of London in the film, and Knole House in Sevenoaks was used in several scenes.[6][7] The home of the Boleyns was represented by Great Chalfield Manor in Wiltshire, and other scenes were filmed at locations in Derbyshire, including Cave Dale, Haddon Hall, Dovedale and North Lees Hall near Hathersage.[8]Dover Castle was transformed into the Tower of London for the execution scenes of George and Anne Boleyn. Knole was the setting for many of the film's London night scenes and the inner courtyard doubles for the entrance of Whitehall Palace where the grand arrivals and departures were staged. The Tudor Gardens and Baron's Hall at Penshurst Place were transformed into the interiors of Whitehall Palace, including the scenes of Henry's extravagant feast.[6]

Historical accuracy[edit]

Historian Alex von Tunzelmann criticized The Other Boleyn Girl for its portrayal of the Boleyn family and Henry VIII, citing factual errors. She stated, "In real life, by the time Mary Boleyn started her affair with Henry, she had already enjoyed a passionate liaison with his great rival, King François I of France. Rather ungallantly, François called her 'my hackney', explaining that she was fun to ride. Chucked out of France by his irritated wife, Mary sashayed back to England and casually notched up her second kingly conquest. The film's portrayal of this Boleyn girl as a shy, blushing damsel could hardly be further from the truth."[9] She further criticized the depiction of Anne as a "manipulative vixen" and Henry as "nothing more than a gullible sex addict in wacky shoulder pads".[9] The film presents other historical inaccuracies, such as the statement of a character that, by marrying Henry Percy, Anne Boleyn would become Duchess of Northumberland, a title that was only created in the reign of Henry's son, Edward VI. Also, it places Anne's time in the French court after her involvement with Percy, something that occurred before the affair.

Release[edit]

Theatrical[edit]

The film was first released in theaters on February 29, 2008, though its world premiere was held at the 58th Berlin International Film Festival held on February 7–17, 2008.[10][11] The film earned $9,442,224 in the United Kingdom,[12] and $26,814,957 in the United States and Canada. The combined worldwide gross of the film was $75,598,644,[12] more than double the film's $35 million budget.

Home media[edit]

The film was released in Blu-ray and DVD formats on June 10, 2008. Extras on both editions include an audio commentary with director Justin Chadwick, deleted and extended scenes, character profiles, and featurettes. The Blu-ray version includes BD-Live capability and an additional picture-in-picture track with character descriptions, notes on the original story, and passages from the original book.

Critical reception[edit]

The film received mixed reviews. Rotten Tomatoes reported that 42% of critics gave the film positive reviews, based on 140 reviews. The site's general consensus is: "Though it features some extravagant and entertaining moments, The Other Boleyn Girl feels more like a soap opera than historical drama."[13]Metacritic reported the film had an average score of 50 out of 100, based on 34 reviews.[14]

Manohla Dargis of The New York Times called the film "more slog than romp" and an "oddly plotted and frantically paced pastiche." She added, "The film is both underwritten and overedited. Many of the scenes seem to have been whittled down to the nub, which at times turns it into a succession of wordless gestures and poses. Given the generally risible dialogue, this isn’t a bad thing."[15]

Mick LaSalle of the San Francisco Chronicle said, "This in an enjoyable movie with an entertaining angle on a hard-to-resist period of history ... Portman's performance, which shows a range and depth unlike anything she's done before, is the No. 1 element that tips The Other Boleyn Girl in the direction of a recommendation ... [She] won't get the credit she deserves for this, simply because the movie isn't substantial enough to warrant proper attention."[16]

Peter Travers of Rolling Stone stated, "The film moves in frustrating herks and jerks. What works is the combustible teaming of Natalie Portman and Scarlett Johansson, who give the Boleyn hotties a tough core of intelligence and wit, swinging the film's sixteenth-century protofeminist issues handily into this one."[17]

Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian awarded the film three out of five stars, describing it as a "flashy, silly, undeniably entertaining Tudor romp" and adding, "It is absurd yet enjoyable, and playing fast and loose with English history is a refreshing alternative to slow and tight solemnity; the effect is genial, even mildly subversive ... It is ridiculous, but imagined with humour and gusto: a very diverting gallop through the heritage landscape."[18]

Sukhdev Sandhu of The Telegraph said, "This is a film for people who prefer their costume dramas to gallop along at a merry old pace rather than get bogged down in historical detail ... Mining relatively familiar material here, and dramatising highly dubious scenarios, [Peter Morgan] is unable to make the set-pieces seem revelatory or tart ... In the end, The Other Boleyn Girl is more anodyne than it has any right to be. It can't decide whether to be serious or comic. It promises an erotic charge that it never carries off, inducing dismissive laughs from the audience for its soft-focus love scenes soundtracked by swooning violins. It is tasteful, but unappetising."[19]

See also[edit]

- The Other Boleyn Girl (2003 film)

- Anne Boleyn in popular culture

References[edit]

^ Mitchell, Wendy (9 March 2007). "A royal welcome". Screen International (Emap Media).

^ "Natalie Portman The Other Boleyn Girl Interview". Girl.com.au. Retrieved June 7, 2009..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Bamigboye, Baz (September 1, 2006). "Scarlett's Royal scandal". Mail Online. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

^ Fischer, Paul. "Bana Takes on Kings and Icons". Film Monthly.com. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

^ "Interview: Eric Bana, The other Boleyn Girl". Get Frank. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

^ ab Kent Film Office. "Kent Film Office The Other Boleyn Girl Film Focus".

^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/kent/content/image_galleries/the_other_boleyn_girl_2008_gallery.shtml BBC Kent website

^ [1][dead link] Ely cathedral was a major location for the film

^ ab von Tunzelmann, Alex (August 6, 2008). "The Other Boleyn Girl: Hollyoaks in fancy dress". The Guardian. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

^ "Berlinale Archive Annual Archives 2008 Programme". Berlin International Film Festival. Retrieved June 17, 2009.

^ Blaney, Martin (January 18, 2008). "Berlinaleadds world premieres including The Other Boleyn Girl". Screen International. Retrieved June 17, 2009.

^ ab "The Other Boleyn Girl (2008) - International Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

^ "The Other Boleyn Girl (2008)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on June 27, 2009. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

^ "Other Boleyn Girl, The (2008): Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

^ Dargis, Manohla (February 29, 2008). "Rival Sisters Duke It Out for the Passion of a King". The New York Times. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

^ LaSalle, Mick (February 29, 2008). "Review: Sisters face off in 'Other Boleyn Girl'". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

^ Travers, Peter (March 20, 2008). "Other Boleyn Girl". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

^ Bradshaw, Peter (March 7, 2008). "The Other Boleyn Girl". guardian.co.uk. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

^ Sandhu, Sukhdev (March 7, 2008). "Film reviews: The Other Boleyn Girl and Garage". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Other Boleyn Girl (2008 film) |

- Official website

The Other Boleyn Girl on IMDb

The Other Boleyn Girl at the TCM Movie Database

The Other Boleyn Girl at AllMovie

The Other Boleyn Girl at Box Office Mojo

The Other Boleyn Girl at Rotten Tomatoes

Categories:

- 2008 films

- English-language films

- 2000s biographical films

- 2000s historical films

- 2000s romantic drama films

- American biographical films

- American films

- American historical films

- American romantic drama films

- BBC Films films

- Biographical films about English royalty

- British biographical films

- British films

- British historical films

- British romantic drama films

- Columbia Pictures films

- Cultural depictions of Anne Boleyn

- Cultural depictions of Elizabeth I of England

- Directorial debut films

- Drama films based on actual events

- Films about Henry VIII of England

- Films based on British novels

- Films produced by Alison Owen

- Films scored by Paul Cantelon

- Films set in London

- Films shot at Elstree Studios

- Films shot at Pinewood Studios

- Films shot in Berkshire

- Films shot in Cambridgeshire

- Films shot in Cornwall

- Films shot in East Sussex

- Films shot in Derbyshire

- Films shot in Gloucestershire

- Films shot in Kent

- Films shot in Somerset

- Films shot in Wiltshire

- Focus Features films

- Historical romance films

- Incest in film

- Mary Boleyn

- Relativity Media films

- Romance films based on actual events

- Screenplays by Peter Morgan

- Universal Pictures films

(window.RLQ=window.RLQ||).push(function(){mw.config.set({"wgPageParseReport":{"limitreport":{"cputime":"0.476","walltime":"0.626","ppvisitednodes":{"value":2434,"limit":1000000},"ppgeneratednodes":{"value":0,"limit":1500000},"postexpandincludesize":{"value":85542,"limit":2097152},"templateargumentsize":{"value":4382,"limit":2097152},"expansiondepth":{"value":22,"limit":40},"expensivefunctioncount":{"value":2,"limit":500},"unstrip-depth":{"value":1,"limit":20},"unstrip-size":{"value":43934,"limit":5000000},"entityaccesscount":{"value":1,"limit":400},"timingprofile":["100.00% 505.939 1 -total"," 36.74% 185.869 1 Template:Reflist"," 24.52% 124.031 16 Template:Cite_web"," 23.23% 117.549 1 Template:Infobox_film"," 21.05% 106.489 1 Template:Infobox"," 9.19% 46.479 1 Template:Official_website"," 7.49% 37.908 1 Template:Dead_link"," 7.01% 35.489 1 Template:IMDb_title"," 6.32% 31.962 1 Template:Fix"," 5.61% 28.402 5 Template:Navbox"]},"scribunto":{"limitreport-timeusage":{"value":"0.211","limit":"10.000"},"limitreport-memusage":{"value":5562555,"limit":52428800}},"cachereport":{"origin":"mw1340","timestamp":"20190115041908","ttl":3600,"transientcontent":true}}});});{"@context":"https://schema.org","@type":"Article","name":"The Other Boleyn Girl (2008 film)","url":"https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Other_Boleyn_Girl_(2008_film)","sameAs":"http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q470073","mainEntity":"http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q470073","author":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Contributors to Wikimedia projects"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Wikimedia Foundation, Inc.","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://www.wikimedia.org/static/images/wmf-hor-googpub.png"}},"datePublished":"2006-09-12T15:12:28Z","dateModified":"2019-01-15T04:19:12Z","image":"https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/7/75/Other_boleyn_girl_post.jpg","headline":"2008 film by Justin Chadwick"}(window.RLQ=window.RLQ||).push(function(){mw.config.set({"wgBackendResponseTime":146,"wgHostname":"mw1262"});});