Lysimachus

Lysimachus

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

| Lysimachus | |

|---|---|

Marble bust of Lysimachus. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli (Archaeological Museum), Italy | |

| King of Thrace | |

| Reign | 306–281 BC |

| Predecessor | Alexander IV |

| Successor | Ptolemy Keraunos |

| King of Asia Minor | |

| Reign | 301–281 BC |

| Predecessor | Antigonus I Monophthalmus |

| Successor | Seleucus I Nicator |

| King of Macedon with Pyrrhus of Epirus | |

| Reign | 288–281 BC |

| Predecessor | Demetrius I Poliorcetes |

| Successor | Ptolemy Keraunos |

| Born | 361 or 355 BC Crannon or Pella |

| Died | February 281 BC (aged 74 or 80) Corupedium, near Sardis |

| Burial | Lysimachia, Thrace |

| Consort |

|

| Issue Among others |

|

| Father | Agathocles |

Lysimachus (Greek: Λυσίμαχος, Lysimachos; c. 360 BC – 281 BC) was a Macedonian officer and diadochus (i.e. "successor") of Alexander the Great, who became a basileus ("King") in 306 BC, ruling Thrace, Asia Minor and Macedon.

Contents

1 Early life and career

2 Diadochi

3 Later years

4 Marriages and children

5 See also

6 References

7 Sources

8 External links

Early life and career[edit]

Lysimachus was born in 361 BC (or 355 BC[1]), to a family of Thessalian Greek stock.[2][3] He was the second son of Agathocles[4] and his wife; there is some indication in the historical sources that this wife was perhaps named Arsinoe, and that Lysimachus' paternal grandfather may have been called Alcimachus. His father was a nobleman of high rank who was an intimate friend of Philip II of Macedon, who shared in Philip II’s councils and became a favourite in the Argead court.[5] Lysimachus and his brothers grew up with the status of Macedonians; all these brothers enjoyed with Lysimachus prominent positions in Alexander’s circle[5] and, like him, were educated at the Macedonian court in Pella.[6][7]

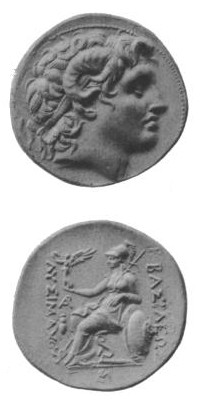

The historian Justin relates the story that Lysimachus smuggled poison to a person Alexander had condemned to a slow death and was himself thrown to a lion as punishment, but overcame the beast with his bare hands and became one of Alexander's favorites. [8]. Some coins issued during Lysimachus's appointment had his image on one side and a lion on the other.

He was probably appointed Somatophylax during the reign of Philip II.[6] During Alexander's Persian campaigns, in 328 BC he was one of his immediate bodyguards.[1] In 324 BC, in Susa, he was crowned in recognition for his actions in India.[9] After Alexander's death in 323 BC, he was appointed to the government of Thrace as strategos[10] although he faced some difficulties from the Thracian Dynasty Seuthes.[1]

Diadochi[edit]

Obverse of coin of Lysimachus: The horned Alexander appears as the king's divine patron.

In 315 BC, Lysimachus joined Cassander, Ptolemy I Soter and Seleucus I Nicator against Antigonus I Monophthalmus, who, however, diverted his attention by stirring up Thracian and Scythian tribes against him.[11] However, he managed to consolidate his power in the east of his territories, suppressing a revolt of the cities on the Black Sea coast.[1]

In 309 BC, he founded Lysimachia in a commanding situation on the neck connecting the Chersonese with the mainland,[11] forming a bulwark against the Odrysians.

In 306/305 BC, Lysimachus followed the example of Antigonus and assumed the royal title.[12]

In 302 BC, when the second alliance between Cassander, Ptolemy and Seleucus was made, Lysimachus, reinforced by troops from Cassander, entered Asia Minor, where he met with little resistance. On the approach of Antigonus he retired into winter quarters near Heraclea, marrying its widowed queen Amastris, a Persian princess. Seleucus joined him in 301 BC, and at the Battle of Ipsus Antigonus was defeated and slain. Antigonus' dominions were divided among the victors. Lysimachus' share was Lydia, Ionia, Phrygia and the north coast of Asia Minor.[13]

Kingdom of Lysimachus

Kingdom of Cassander

Kingdom of Seleucus I Nicator

Kingdom of Ptolemy I Soter

Epirus

Carthage

Rome

Greek colonies

Feeling that Seleucus was becoming dangerously powerful, Lysimachus now allied himself with Ptolemy, marrying his daughter Arsinoe II of Egypt. Amastris, who had divorced herself from him, returned to Heraclea. When Antigonus' son Demetrius I renewed hostilities (297 BC), during his absence in Greece, Lysimachus seized his towns in Asia Minor, but in 294 BC concluded a peace whereby Demetrius was recognized as ruler of Macedonia. He tried to carry his power beyond the Danube, but was defeated and taken prisoner by the Getae king Dromichaetes (or Dromihete), who, however, set him free in 292 BC on amicable terms in return for Lysimachus surrendering the Danubian lands he had captured.[1] Demetrius subsequently threatened Thrace, but had to retire due to a sudden uprising in Boeotia and an attack from King Pyrrhus of Epirus.[11]

In 287 BC, Lysimachus and Pyrrhus in turn invaded Macedonia and drove Demetrius out of the country. Lysimachus left Pyrrhus in possession of Macedonia with the title of king for around seven months before Lysimachus invaded.[11] For a short while the two ruled jointly but in 285 BC Lysimachus expelled Pyrrhus, seizing complete control for himself.[14]

Tetradrachm of Lysimachus. The Greek inscription reads: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΛΥΣΙΜΑΧΟΥ "[coin] of King Lysimachus".

Later years[edit]

Domestic troubles embittered the last years of Lysimachus’ life. Amastris had been murdered by her two sons; Lysimachus treacherously put them to death. On his return, Arsinoe II asked the gift of Heraclea, and he granted her request, though he had promised to free the city. In 284 BC Arsinoe, desirous of gaining the succession for her sons in preference to Lysimachus’ first child, Agathocles, intrigued against him with the help of Arsinoe's paternal half-brother Ptolemy Keraunos; they accused him of conspiring with Seleucus to seize the throne, and Agathocles was put to death.[11]

This atrocious deed by Lysimachus aroused great indignation. Many of the cities of Asia Minor revolted, and his most trusted friends deserted him. The widow of Agathocles and their children fled to Seleucus, who at once invaded the territory of Lysimachus in Asia Minor. In 281 BC, Lysimachus crossed the Hellespont into Lydia and at the decisive Battle of Corupedium was killed. After some days his body was found on the field, protected from birds of prey by his faithful dog.[15] Lysimachus' body was given over to another son, Alexander, by whom it was interred at Lysimachia.[11]

Marriages and children[edit]

Lysimachus was married three times and his wives were:

- First marriage: Nicaea a Greek (Macedonian) noblewoman and daughter of the powerful Regent Antipater. Lysimachus and Nicaea married in c. 321 BC. Nicaea bore Lysimachus three children:

- Son, Agathocles[16][17]

- Daughter, Eurydice[16][17]

- Daughter, Arsinoe I[16][17]

- Son, Agathocles[16][17]

Nicaea most probably died by 302 BC.

- Second marriage: Persian Princess Amastris. Lysimachus married her in 302 BC. Amastris and Lysimachus’ union was brief, as he ended their marriage and divorced her in 300/299 BC.

- Third marriage: Ptolemaic Greek Princess Arsinoe II. Arsinoe II married Lysimachus in 300/299 BC and remained with him until his death in 281 BC. Arsinoe II bore Lysimachus three sons:

Ptolemy I Epigonos[16][18][19]

Lysimachus[16]

Philip[16]

From an Odrysian concubine he had a son borne to him called Alexander.[20]

See also[edit]

- Belevi Mausoleum

References[edit]

^ abcde Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Tony (2000). Who's Who in the Classical World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 238. ISBN 0192801074..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Sear, David R. (1978). Greek Coins and Their Values, Volume 2. Seaby. p. 634. ISBN 9780900652509.Lysimachos, 323–281 B.C. (one of the most remarkable of the 'Successors' of Alexander, Lysimachos was of Thessalian stock and was a bodyguard of the great Macedonian King.

^ Traver, Andrew G. (2002). From Polis to Empire, the Ancient World, C. 800 B.C.-A.D. 500: A Biographical Dictionary. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 236. ISBN 9780313309427.Lysimachus was a citizen of Pella in Macedonia, although his father was said to have been a Greek from Thessaly.

^ Lund, Lysimachus: A Study in Early Hellenistic Kingship, p. 3

^ ab Lund, Lysimachus: A Study in Early Hellenistic Kingship, p.2

^ ab Heckel, Who’s who in the age of Alexander the Great: prosopography of Alexander’s empire, p. 153

^ Lysimachus had an elder brother called Alcimachus of Apollonia and had two younger brothers called Autodicus and Philip. He had two known nephews through his brother Alcimachus called Alcimachus and Philip; his known great-nephew was Lysippus the grandson of his brother Alcimachus and his known sister-in-law was Adeia the wife of Autodicus

^ http://www.attalus.org/translate/justin1.html#15.1 Justin, Epitome of Pompey Trogue’s “Philippic histories”, XV, 3, 1–9: Retrieved 18 January 2019

^ Heckel, Who's Who in the Age of Alexander the Great: Prosopography of Alexander's Empire pp. 153-154. "Near Sangala in India some 1,200 of Alexander's troops were wounded, among them Lysimachus the Somatophylax. He had earlier boarded a thirty-oared vessel at the Hydaspes (in the company of two other Somatophylakes), before the battle with Porus, though his role in the actual battle is not attested; presumably he fought in the immediate vicinity of Alexander himself. When Alexander decided to sail down the Indus river system to the Ocean, Lysimachus was one of those from Pella charged with a trierarchy in the Attic fashion. He is named by Arrian in the only complete list of Somatophylakes. At Susa in spring 324 BC, Lysimachus and the rest of the Somatophylakes were crowned by Alexander, though unlike Leonnatus, Lysimachus appears to have earned no special distinction."

^ Heckel, Who's Who in the Age of Alexander the Great: Prosopography of Alexander's Empire p. 155." In 323 Lysimachus was assigned control of Thrace, and was probably strategos rather than satrap. The subordinate position of strategos may account for the failure of the sources to mention Lysimachus in the settlement of Triparadeisus; his brother Autodicus was, however, named as a Somatophylax of Philip III at that time."

^ abcdef One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 184.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 184.

^ Heckel, Who's Who in the Age of Alexander the Great: Prosopography of Alexander's Empire, p. 155. "In 306 or 305 BC, he assumed the title of "King", which he held until his death at Corupedium in 282/1 BC."

^ Williams, Henry Smith. Historians History of the World (Volume 4), p. 450.

^ Williams, Henry Smith. Historians History of the World (Volume 4), p. 454.

^ Williams, Henry Smith. Historians History of the World (Volume 4), p. 505.

^ abcdef Bengtson, Griechische Geschichte von den Anfängen bis in die römische Kaiserzeit, p.569

^ abc Heckel, Who’s who in the age of Alexander the Great: prosopography of Alexander’s empire, p.175

^ Billows, Kings and colonists: aspects of Macedonian imperialism, p. 110

^ Ptolemaic Genealogy: Ptolemy ‘the Son’, Footnotes 9 & 12

^ Pausanias, 1.10.4

Sources[edit]

Arrian, Anabasis v. 13, vi. 28

Justin xv. 3, 4, xvii. I

Quintus Curtius Rufus V. 3, x. 30

Diodorus Siculus xviii. 3

Polybius v. 67

Plutarch, Demetrius, 31. 52, Pyrrhus, 12

Appian, Syriaca, 62

Connop Thirlwall, History of Greece, vol. viii. (1847)

John Pentland Mahaffy, Story of Alexander’s Empire

Johann Gustav Droysen, Hellenismus (2nd ed., 1877)- Adolf Holm, Griechische Geschichte, vol. iv. (1894)

Benedikt Niese, Geschichte der griechischen und makedonischen Staaten, vols. i. and ii. (1893, 1899)

Karl Julius Beloch, Griechische Geschichte vol. iii. (1904)- Hunerwadel, Forschungen zur Gesch. des Könige Lysimachus (1900)

- Possenti, Il Re Lisimaco di Tracia (1901)

- Ghione, "Note sul regno di Lisimaco" (Atti d. real. Accad. di Torino, xxxix.)

- H. Bengtson, Griechische Geschichte von den Anfängen bis in die römische Kaiserzeit, C.H.Beck, 1977

- R.A. Billows, Kings and colonists: aspects of Macedonian imperialism, BRILL, 1995

- H.S. Lund, Lysimachus: A Study in Early Hellenistic Kingship, Routledge, 2002

- W. Heckel, Who’s who in the age of Alexander the Great: prosopography of Alexander’s empire, Wiley-Blackwell, 2006

- Lysimachus’ article at Livius.org

- Ptolemaic Genealogy: Ptolemy Ceraunus

- Ptolemaic Genealogy: Unknown wife of Ptolemy Ceraunus

- Ptolemaic Genealogy: Ptolemy ‘the Son’

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lysimachus. |

- Lysimachus

Lysimachus' Dog & Nisaean Horses – Informative but non-scholarly essay on Lysimachus (Annotated with Sources)

| Preceded by New creation | Governor of Thrace 323–306 BC | Succeeded by Merged into kingship |

| Preceded by Alexander IV | King of Thrace 306–281 BC | Succeeded by Ptolemy Keraunos |

| Preceded by Antigonus I Monophthalmus | King of Asia Minor 301–281 BC | Succeeded by Seleucus I Nicator |

| Preceded by Demetrius I Poliorcetes | King of Macedon with Pyrrhus of Epirus 288–281 BC | Succeeded by Ptolemy Keraunos |

Categories:

- 360s BC births

- 281 BC deaths

- 3rd-century BC Macedonians

- 4th-century BC Macedonians

- 3rd-century BC Macedonian monarchs

- 3rd-century BC rulers

- 4th-century BC rulers

- Ancient Greeks killed in battle

- Ancient Macedonian generals

- Ancient Pellaeans

- Ancient Thessalians in Macedon

- Deaths by javelin

- Hellenistic generals

- Hellenistic Macedonia

- Hellenistic rulers

- Hellenistic Thrace

- Macedonian monarchs

- Macedonian monarchs killed in battle

- Non-dynastic kings of Macedonia (ancient kingdom)

- Satraps of the Alexandrian Empire

- Somatophylakes

- Trierarchs of Nearchus' fleet

(window.RLQ=window.RLQ||).push(function(){mw.config.set({"wgPageParseReport":{"limitreport":{"cputime":"0.816","walltime":"1.120","ppvisitednodes":{"value":4070,"limit":1000000},"ppgeneratednodes":{"value":0,"limit":1500000},"postexpandincludesize":{"value":99303,"limit":2097152},"templateargumentsize":{"value":10743,"limit":2097152},"expansiondepth":{"value":9,"limit":40},"expensivefunctioncount":{"value":6,"limit":500},"unstrip-depth":{"value":1,"limit":20},"unstrip-size":{"value":30005,"limit":5000000},"entityaccesscount":{"value":1,"limit":400},"timingprofile":["100.00% 814.867 1 -total"," 22.72% 185.175 1 Template:Reflist"," 18.14% 147.857 3 Template:Navbox"," 16.22% 132.177 1 Template:Diadochi"," 15.73% 128.139 1 Template:Infobox_royalty"," 13.57% 110.583 1 Template:Commons_category"," 12.80% 104.285 3 Template:Cite_book"," 12.07% 98.356 1 Template:Infobox"," 8.00% 65.188 1 Template:Authority_control"," 6.91% 56.328 4 Template:Succession_box"]},"scribunto":{"limitreport-timeusage":{"value":"0.264","limit":"10.000"},"limitreport-memusage":{"value":5085388,"limit":52428800}},"cachereport":{"origin":"mw1258","timestamp":"20190126153008","ttl":2073600,"transientcontent":false}}});});{"@context":"https://schema.org","@type":"Article","name":"Lysimachus","url":"https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lysimachus","sameAs":"http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q32133","mainEntity":"http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q32133","author":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Contributors to Wikimedia projects"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Wikimedia Foundation, Inc.","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://www.wikimedia.org/static/images/wmf-hor-googpub.png"}},"datePublished":"2003-06-19T05:48:12Z","dateModified":"2019-01-19T12:31:09Z","image":"https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f1/Lisimaco_%28c.d.%29%2C_copia_augustea_%2823_ac-14_dc%29_da_orig._del_II_sec_ac._6141.JPG","headline":"Macedonian officer"}(window.RLQ=window.RLQ||).push(function(){mw.config.set({"wgBackendResponseTime":1329,"wgHostname":"mw1258"});});