White Rajahs

Other men sometimes referred to as White Rajahs include Englishman Alexander Hare in Borneo, Scot John Clunies Ross in the Cocos Islands, and Dane Mads Lange in Bali. For the book by Nigel Barley, see Nigel Barley (anthropologist)

| Rajah of Sarawak | |

|---|---|

Coat of arms | |

HH James Brooke, Rajah of Sarawak | |

| Details | |

| Style | His Highness |

| First monarch | James Brooke |

| Last monarch | Charles Vyner Brooke |

| Formation | 1841 |

| Abolition | 1946 |

| Residence | The Astana |

| Pretender(s) | James Brooke |

The White Rajahs were a dynastic monarchy of the British Brooke family, who founded and ruled the Kingdom of Sarawak, located on the north west coast of the island of Borneo, from 1841 to 1946. The first ruler was an Englishman James Brooke. As a reward for helping the Sultanate of Brunei fight piracy and insurgency among the indigenous peoples, he was granted the province of Kuching which was known as Sarawak Asal (Original Sarawak) in 1841 and received independent kingdom status.

Based on descent through the male line in accordance with the Will of Sir James Brooke, the White Rajahs' dynasty continued through Brooke's nephew and grandnephew, the latter of whom ceded his rights to the United Kingdom in 1946. His nephew had been the legal heir to the throne and objected to the cession, as did most of the Sarawak members of the Council Negri.

Contents

1 Rulers

2 Titles

3 Line of Succession

4 Government

5 Cession to the United Kingdom

6 Legacy

7 Heraldry and emblems

8 See also

9 References

10 External links

Rulers

Sarawak was part of the realm of Brunei until 1841 when James Brooke was granted a sizeable area of land in the southwest area of Brunei – around the town of Sarawak (now Kuching) and the nearby mining region of Bau – from Bruneian Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin II. He was later confirmed with the title of Rajah of the territory. The Kingdom of Sarawak developed and expanded during the rule of the first two White Rajahs, growing to occupy much of the north region of the island of Borneo. The Brooke administrations leased or annexed more land from Brunei.

The White Rajahs were all related:

| Name | Portrait | Birth | Death | Marriages | Succession right |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

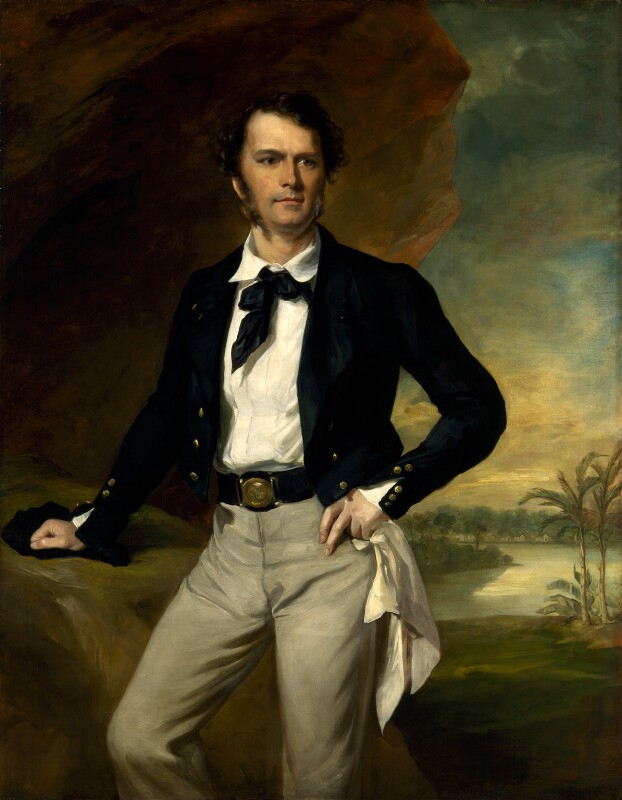

James of Sarawak (James Brooke) (1841–1868) |  | 29 April 1803, India | 11 June 1868, England | unmarried, but acknowledged an illegitimate son | granted Sarawak and the title Rajah by the Sultan of Brunei |

John Brooke Johnson/Brooke Rajah Muda of Sarawak (1859–1863) |  | 1823, England | 1 December 1868, England | Anne Grant, children: Basil, John Evelyn Hope Julia Welstead, child: Matilda Agnes | His uncle James regarded him as heir from at least 1848, formally installed him as Rajah Mudah in 1859, but disinherited him for what he termed 'treason' |

Charles of Sarawak (Charles Johnson/Brooke) (1868–1917) |  | 3 June 1829, England | 17 May 1917, England | Dayang Mastiah, one illegitimate son, Esca (sent to Canada and received an allowance) Margaret Alice Lili de Windt, with whom he had six children; three survived infancy More illegitimate children have been suspected but not acknowledged | His uncle James named Charles as his successor in 1865 |

Vyner of Sarawak (Charles Vyner Brooke) (1917–1946) |  | 26 September 1874, England | 9 May 1963, England | Sylvia Brett, with whom he had three daughters | son of the preceding, inherited the title |

Bertram of Sarawak (Bertram Brooke) Tuan Muda of Sarawak (1917–1946) | 8 August 1876, Sarawak | 15 September 1965, England | Gladys Palmer, with whom he had three daughters and one son | brother of the preceding | |

Anthony of Sarawak (Anthony Brooke) Rajah Muda of Sarawak (1939–1946) | 10 December 1912, England | 2 March 2011, New Zealand | Kathleen Hudden, with whom he had two daughters and one son | son of the preceding. Disinherited as Rajah Muda in 1946 by the British Government |

Graves of the White Rajahs at St Leonard's Church, Sheepstor, Devon, England.

James and Charles had short grammar school educations, Vyner, Bertram, and Anthony went to public schools and Cambridge University (but without taking degrees). All but Anthony died in England and are buried at Sheepstor parish church, Devon. Anthony Brooke had his ashes interred at Sheepstor as well as at the Brooke Family graveyard in Kuching, as per his last wish.

The White Rajahs pursued a policy of paternalism, with the goal of protecting the "native peoples" (indigenous peoples) from "capitalist exploitation". While James Brooke laid much of the groundwork for the expansion of Sarawak, his nephew Charles, the second Rajah, was the great builder. He constructed public buildings to serve welfare, such as a hospital, in addition to forts. He worked to extend the borders of the state.

Vyner Brooke instituted significant political reforms during his tenure. He ended the absolute rule of the Rajah in 1941, before the Japanese invasion of World War II, by granting new powers to the Council Negri (the parliament). Bertram co-ruled with his elder brother, taking turns of 6 – 8 months in charge of the country each year. By 1939 Bertram's son Anthony had taken the reins of government, and it was with a considerable controversy that Vyner attempted to cede Sarawak to Britain secretly in 1946 in what gave rise to the anti-cession movement of Sarawak.

Titles

The Sovereign: His Highness The Rajah of Sarawak

The consort of the ruling prince: Her Highness The Ranee of Sarawak

The Heir Apparent: His Highness The Rajah Muda of Sarawak

Wife of the Heir Apparent: Her Highness The Ranee Muda of Sarawak

The Heir Presumptive: His Highness The Tuan Muda of Sarawak

Wife of the Heir Presumptive: Her Highness The Dayang Muda of Sarawak

Daughters of the Sovereign and his heirs: Dayang (personal name).[1]

Line of Succession

In accordance with the Will of the first Rajah, Sir James Brooke, the line of succession to the 'sovereignty of Sarawak and all the rights and privileges whatsoever thereto belonging,' was to the heirs male lawfully begotten of the Rajah's nephew Charles Anthony Johnson Brooke. Charles inherited under the Will in 1868, and confirmed the succession in his own will of 1913. On his accession in 1918, his son Vyner (later Sir Charles Vyner Brooke, Rajah of Sarawak) swore to uphold the Will 'as forming the constitution of the state'. This unique testamentary trust became known as 'The Sarawak Sovereignty Trust'.

The Brooke Dynasty Tree

Government

Brooke Memorial outside the Old Courthouse at Kuching showing relief of Iban warrior

When James Brooke first arrived in Sarawak, it was governed as a vassal state of the Sultanate of Brunei; the system of government was based on the Bruneian model. Brooke reorganised the government according to the British model, eventually creating a civil service. It recruited European, chiefly British, officers to run district outstations. The Sarawak Service was continually reformed by Rajah James and his successors.

Rajah James retained many of the customs and symbols of Malay monarchy, and combined them with his own style of absolute rule. The Rajah had the power to introduce laws and acted as chief judge in Kuching.

The White Rajahs were determined to prevent the indigenous peoples of Sarawak from being exploited by Western business interests. They allowed the Borneo Company Limited (the Borneo Company) to assist in managing the economy. The core of the early Sarawak economy was antimony, later followed by gold, which was mined in Bau by Chinese syndicates who imported numerous workers from China.[2] After the local Chinese uprising in 1857,[3] the mining operations were gradually taken over by the Borneo Company; it bought out the last Chinese syndicate in 1884.[2] The Borneo Company provided military support to the White Rajahs during crises such as the Chinese uprising. One of the company steamships, the Sir James Brooke, helped recapture Kuching.

Rajah Charles formed a small paramilitary force, the Sarawak Rangers, to police and defend the expanding state. This small army also manned a series of forts around the country, acted as the Rajahs' personal guard, and performed ceremonial duties.

Cession to the United Kingdom

After the Second World War, during which Sarawak and Borneo had been occupied by Japanese forces, the third rajah, Vyner Brooke, ceded his life interest in Sarawak to the Colonial Office. Unclear as to the legality of cession, the British Government simultaneously passed a Bill of Annexation. Rajah Vyner's nephew and legal heir, Anthony Brooke, initially opposed annexation by the Crown, as did a majority of the native members of the Council Negri.

Because of his opposition to the cession, Anthony Brooke was considered a suspect when Duncan Stewart, the second British governor to Sarawak, was assassinated by two people that were believed to be members of a group dedicated to restoring him as Rajah.[4] In fact, they were from a political group agitating for union with newly independent Indonesia.[4] He was never prosecuted. Documents released in the late 20th century indicate that the British Government knew that Brooke was not involved, but chose not to reveal the truth of the matter so not to provoke Indonesia. It had recently won its war of independence from the Netherlands, and the UK was already dealing with the Malayan Emergency to the north-west.[4][5] Since those events, there has been no serious movement for the restoration of the monarchy, although under the Will of Sir James Brooke any member of the Brooke family is eligible to be appointed heir.

The period of Brooke rule is generally looked upon favourably in Sarawak, and in recent times the government has accepted the importance of their legacy for its social, cultural, and touristic value.

The Brooke family still maintains strong ties to the state and its people and are represented by the Brooke Trust, and by Anthony Brooke's grandson Jason Desmond Anthony Brooke, at many state functions and supporting heritage projects.

Legacy

Fort Margherita was erected by Rajah Charles and named after his wife, the Ranee Margaret.

- The coaling station of Brooketon in Brunei was named after the Brooke family.

- The architectural legacy of the dynasty can be seen in many of the country's 19th-century and colonial heritage buildings. In Kuching these include the Astana, or governor's residence; the Sarawak Museum, the Old Courthouse, Fort Margherita, the Square Fort, and Brooke Memorial. The Brooke Dockyard, which was founded in the period of Rajah Charles, is still in operation, as is the original Sarawak Museum. Several key buildings from the Brooke period, such as the offices and warehouses of Borneo Company, have been demolished for more recent developments.

Modern Kuching has many businesses and attractions that refer to the era of the White Rajahs:

- The James Brooke Café and the Royalist, a pub named after James Brooke's schooner, refer to the history of the Brookes.

- The Brooke Gallery which showcases belongings from the Brooke family and artifacts during their time as the White Rajah. The gallery is located in Fort Margherita.

Sarawak has a diverse population with a large proportion of indigenous tribal peoples, such as the Iban and other Dyaks. In addition, it received numerous Chinese and Indian immigrants, whose businesses and labour were encouraged at various times by the White Rajahs.

Heraldry and emblems

Flag of the Kingdom of Sarawak.

The heraldic arms of the Brooke dynasty were based on the emblem used by James Brooke. It consisted of a red and black cross on a yellow shield, crested by a badger, known in heraldic parlance as a "brock" and hence alluding to the dynastic surname. A crown was added in 1949, and the shield design was used as the basis of the Sarawak flag until 1973. In 1988 the state flag reverted to these original colours.

See also

- Kingdom of Sarawak

- List of Sarawakian consorts

- List of heads of government of the Kingdom of Sarawak

References

^ http://www.royalark.net/Malaysia/sarawak.htm

^ ab Kaur, Amarjit (February 1995). "The Babbling Brookes: Economic Change in Sarawak 1841–1946". Modern Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 29 (1): 65–109, 73. doi:10.1017/s0026749x00012634. ISSN 0026-749X..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Chew, Daniel (1990). Chinese Pioneers on the Sarawak Frontier 1841–1941. Singapore: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-588915-0.

^ abc Mike Thomson (14 March 2012). "The stabbed governor of Sarawak". bbc.co.uk. BBC News. Retrieved 2016-11-04.

^ Mike Thomson (12 March 2012). "Radio 4's investigative history - The stabbed governor of Sarawak". bbc.co.uk. BBC News. Retrieved 2016-11-04.

Ranee Margaret of Sarawak (2001). My Life in Sarawak. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-582663-9.

Sylvia, Lady Brooke (1970). Queen of the Headhunters.

Eade, Philip (2007). Sylvia, Queen of the Headhunters: A Biography of Lady Brooke, the Last Ranee of Sarawak. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Reece, R.H.W. (1993). The Name of Brooke: The End of White Rajah Rule in Sarawak.

Runciman, Steven (1960). The White Rajahs: A History of Sarawak from 1841 to 1946. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schutte, O (1981). "M. R. H. Calmeyer, de Wind, de Windt, de Wint". De Nederlandsche Leeuw. p. 23.

"Quast". Nederlandse Genealogieen. 11. Den Haag: Koninklijk Genootschap voor Geslacht- en Wapenkunde. 1996. (Literature regarding Broek-De Wind)

External links

- brooketrust.org

- Old Rajah Brooke website (snapshot from 9 June 2009)

- A Sarawak Royal Interest Homepage

- bbc.co.uk

- rajahofsarawakfund